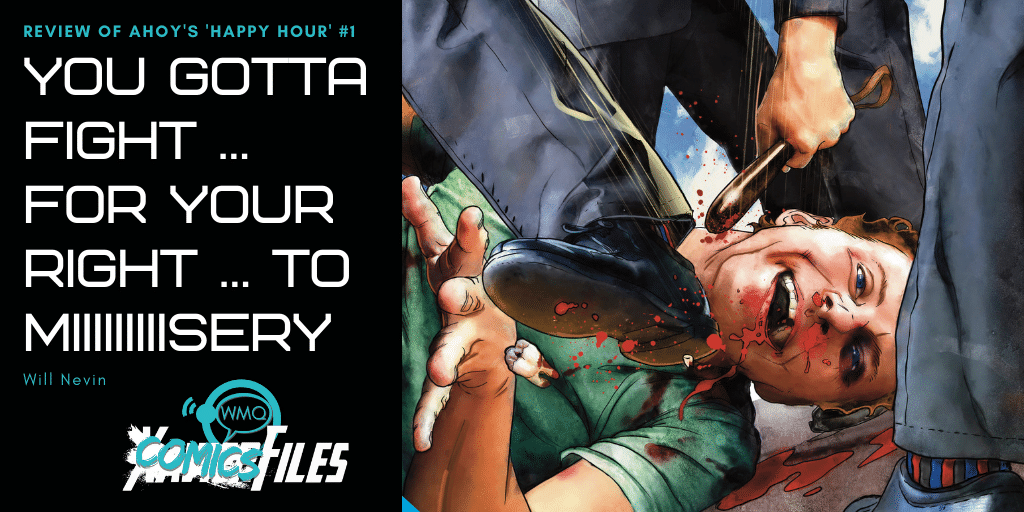

Happy Hour #1

Writer: Peter Milligan, Artist: Michael Montenat, Colorist: Felipe Sobreiro, Letterer: Rob Steen, Publisher: AHOY

It’s 12:48 a.m. Central Standard Time. I am watching what seems to be my 86th consecutive hour of MSNBC (because it is a Rick Santorum-free zone), but all I really want is to go to bed.

Well, that’s a lie. What I really want is to open my bottle of 12-year-old Pappy Van Winkle bourbon, pour a precious few fingers and sip slowly the spiced caramel elixir of satisfaction.

I want to drink and — for a moment — feel good. I want to forget about the things I have to do tomorrow. I want permission to enjoy this win.

I want to be happy.

Not that I’m not happy, of course.

It’s 12:56 a.m. Chris Hayes has signed off. Quitter.

But it’s that ability to let go, to fall into unchecked glee, that feels so good. To celebrate.

That’s what I want.

The B-team is in the studio. Bah. At least Steve Kornacki is still here.

Happiness is a fleeting thing in sports and politics and all other flavors of life, and perhaps that’s what makes it so good and warm and wonderful — because it is so ephemeral. It never lasts. Therefore, it’s incumbent upon us to hold onto those flashes and glints of light. But that’s the problem with something you can’t actually clutch, isn’t it?

That preciousness makes it worthwhile. But to think that there might ever be a situation in which we’re required to be happy? That’s unsettling. Queasily so. And yet that’s the premise of “Happy Hour,” the latest comic funny book from AHOY that’s not so laugh-out-loud hilarious as it is a biting satire of life and culture and what that titular feeling (and its absence) really means.

1:39 a.m.: We’re talking about a presidential tweet. I don’t remember when there was a new vote total from Georgia or Pennsylvania, but there is an ad for Alien Tape, which is at least more entertaining than the commercials for adult undergarments and hokum-like apple cider vinegar gummies. This is not happening tonight. The overall win, I mean. Although the president’s lead is down to 665 votes in Georgia. I could drink to that, right?

Jerry is a guy in a radically dystopian society in which no one is allowed to be sad at any time — this ban on grumpiness includes situations where it would be altogether normal, such as the aftermath of a car accident that kills Jerry’s sister and necessitates the brain surgery that scrambles his ability to abide by the established order. When he awakes, everyone is still smiles and laughs, but now, he no longer understands how or why the world is the way that it is. This sets Jerry apart from the rest of the (fake) happy society and sets the machinery of the government upon him.

2:13 a.m: There’s a commercial for Christmas decor at Michael’s. One holiday at a time.

The First Amendment scholar in me sees the bones of so many unsuccessful attempts to limit speech in this comic. Hustler v. Falwell gave us the right to say the most unimaginably mean things about celebrities and others in the public eye without fear of civil liability. U.S. v. Alvarez enshrined a limited right to straight up lie about important moral matters like military service. And Snyder v. Phelps allowed one bigoted cult to say the most vile things about a solider who died in service of his country.

2:54 a.m.: 463 votes.

But as I always tell my students, one of the most instructive ways to think about the First Amendment comes from “Ghostbusters 2.” (Really.) It’s a scene where Egon and the fellas are huddling with the New York mayor, explaining the dangers of the evil slime river under the city. Mayor, they tell him, you’ve got to do something to get the people of the city to be nicer to each other. It’s an emergency, the ‘Busters say, one that can only be abated by kindness.

The mayor refuses to ask the people of the city to change.

“Being miserable and treating other people like dirt,” he says, “is every New Yorker’s God-given right.”

I typically misquote that as “It’s every New Yorker’s God-given eight to be an asshole,” but the substance is the same. The First Amendment does not necessitate good speech or friendliness. It does not require us to be nice to each other.

And it certainly does not mandate happiness.

So to see a dark and contrary vision reflected so clearly in “Happy Hour” is unnerving not because it necessarily represents the world of tomorrow but because it speaks to the ripple of thought that will always be with us: that it’s somehow within the government’s powers to engineer a better society via speech alone rather than changing any of the substantive conditions causing the underlying misery.

3:26 a.m.: Now a 917-vote lead in Georgia for the challenger. The feeling bubbles up. I break out the all caps on Twitter. But it passes. I cannot be happy enough.

3:55 a.m.: Steve Kornacki says he’s staying to see a winner. I don’t know if I can.

There is probably something here about mental health — there’s simply too much time spent in government treatment centers with “re-education” tools that look like torture for there not to be. But as of this first issue, I’m not sure that I can parse out the book’s position on it or even if it really has a stand to make. What I will say as someone whose life has been touched by family members with mental illness is that I believe in the field: that if you have the right doctor and the right therapies, your life can be better. To the extent that this series might poke back against this or pharmacological interventions generally, I can’t support that stance, but again, it is late, and I am tired and perhaps I’m reading something into this.

5:02 a.m.: Steve Kornacki got an hour off. Good for him.

*The* call will not come in the next hour, which is probably the outside limit of how much longer I can stay awake. And that’s fine. Real, earned and blessedly fleeting happiness is better than the fake and the forced. I can wait.

And so will the Pappy.

Will Nevin loves bourbon and AP style and gets paid to teach one of those things. He is on Twitter far too often.